1. Pegasus Spyware Reportedly Hacked iPhones of U.S. State Department and Diplomats

Apple reportedly notified several U.S. Embassy and State Department employees that their iPhones may have been targeted by an unknown assailant using state-sponsored spyware created by the controversial Israeli company NSO Group, according to multiple reports from Reuters and The Washington Post.

At least 11 U.S. Embassy officials stationed in Uganda or focusing on issues pertaining to the country are said to have singled out using iPhones registered to their overseas phone numbers, although the identity of the threat actors behind the intrusions, or the nature of the information sought, remains unknown as yet.

The attacks, which were carried out in the last several months, mark the first known time the sophisticated surveillance software has been put to use against U.S. government employees.

NSO Group is the maker of Pegasus, military-grade spyware that allows its government clients to stealthily plunder files and photos, eavesdrop on conversations, and track the whereabouts of their victims. Pegasus uses zero-click exploits sent through messaging apps to infect iPhones and Android devices without requiring targets to click links or take any other action, but are by default blocked from working on U.S. phone numbers.

In response to the reports, the NSO Group said it will investigate the matter and take legal action, if necessary, against customers for using its tools illegally, adding it had suspended „relevant accounts,” citing the „severity of the allegations.”

It’s worth noting that the company has long maintained it only sells its products to government law enforcement and intelligence clients to help monitor security threats and surveil terrorists and criminals. But evidence gathered over the years has revealed a systematic abuse of the technology to spy on human rights activists, journalists and politicians from Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Morocco, Mexico, and other countries.

NSO Group’s actions have cost it dear, landing it in the crosshairs of the U.S. Commerce Department, which placed the company in an economic blocklist last month, a decision that may have been motivated by the aforementioned targeting of U.S. foreign diplomats.

Furthermore, tech giants Apple and Meta have since waged a legal onslaught against the company for illegally hacking their users by exploiting previously unknown security flaws in iOS and the end-to-end encrypted WhatsApp messaging service. Apple, in addition, also said it began sending threat notifications to alert users it believes have been targeted by state-sponsored attackers on November 23.

To that end, the notifications will be delivered to affected users via email and iMessage to the addresses and phone numbers associated with the users’ Apple IDs, and a prominent „Threat Notification” banner will be displayed at the top of the page when impacted users log into their accounts on appleid.apple[.]com.

„State-sponsored actors like the NSO Group spend millions of dollars on sophisticated surveillance technologies without effective accountability,” Apple’s software engineering chief Craig Federighi previously said. „That needs to change.”

The disclosures also coincide with a report from The Wall Street Journal that detailed the U.S. government plans to work with over 100 countries to limit the export of surveillance software to authoritarian governments that use the technologies to suppress human rights. China and Russia are not expected to be a part of the new initiative.

2. Why Everyone Needs to Take the Latest CISA Directive Seriously

Government agencies publish notices and directives all the time. Usually, these are only relevant to government departments, which means that nobody else really pays attention. It’s easy to see why you would assume that a directive from CISA just doesn’t relate to your organization.

But, in the instance of the latest CISA directive, that would be making a mistake. In this article, we explain why, even if you’re in the private or non-government sector, you should nonetheless take a close look at CISA Binding Operational Directive 22-01.

We outline why CISA was forced to issue this directive, and why that firm action has implications for all organizations – inside and outside of government. Acting on cybersecurity issues isn’t as simple as flicking a switch, of course, so keep reading to find out how you can address the core issue behind the CISA directive.

Okay, so what exactly is a CISA directive?

Let’s take a step back to gain some context. Just like any organization that uses technology, US government agencies – federal agencies – are constantly under cyberattack from malicious actors, from common criminals to enemy states.

As a result, the US Department of Homeland Security set up CISA, the Cybersecurity, and Infrastructure Security Agency, to help coordinate cybersecurity for federal agencies.

CISA says that it acts as the operational lead for federal cybersecurity, defending federal government networks. But each agency has its own operational and technology teams that are not under the direct control of CISA – and that’s where the CISA directives come in.

A CISA directive is intended to compel tech teams at federal agencies to take certain actions that CISA deems necessary to ensure safe cybersecurity operations. The directives generally deal with specific, high-risk vulnerabilities but some directives are more general, with BD 18-01, for example, outlining specific steps agencies should take to improve email security.

What does directive BD 22-01 say?

Binding operational directive 22-01 is one of the broader directives – in fact, it’s very broad, referring to over three hundred vulnerabilities. It’s a dramatic step for CISA to take – it’s not just another run-of-the-mill communications message.

With this directive, CISA presents a list of vulnerabilities that it thinks are the most commonly exploited within the larger field of tens of thousands of known vulnerabilities. Some of these vulnerabilities are quite old.

In this vulnerability catalog, each entry specifies a fixed date whereby federal agencies need to remediate the vulnerability. Within the directive itself are further detailed instructions and timelines – including establishing a process to regularly review the list attached to BD 22-01 – meaning this list will be expanded in the future.

Examples of vulnerabilities on the list

Let’s look at some examples of vulnerabilities on this list. CISA rounded up what are, in its view, the most serious, most exploited vulnerabilities – in other words, vulnerabilities that are most likely to lead to harm if not addressed.

The list covers a really wide scope, from infrastructure through to applications – including mobile apps – even covering some of the most trusted security solutions. It includes vendors such as Microsoft, SAP, and TrendMicro as well as popular open-source technology solutions including Linux and Apache.

One example of a vulnerability on the list relates to the Apache HTTP Server, where a range of release 2.4 versions is affected by a scoreboard vulnerability – CVE-2019-0211. It allows attackers to start an attack by running code in a less privileged process that manipulates the scoreboard, enabling the execution of arbitrary code with the permissions of the parent process.

Another example lies in Atlassian Confluence, the popular collaboration tool. Here, attackers can mount a remote code execution attack by injecting macro code into the Atlassian Widget Connector. Again, this vulnerability is listed by CISA because the organization deemed that it was commonly exploited.

Yes! This CISA directive applies to you too…

Okay, CISA’s directives can’t be enforced on technology teams outside of the US federal government, but that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to learn here.

To start, take a step back and think about CISA’s reasoning before you simply dismiss its latest directive. We know that cybersecurity attacks are commonplace and that the costs are enormous, whether you’re operating within a state or federal environment – or as a private enterprise.

CISA only published this list as a last resort. The agency became so exasperated with attackers frequently hitting government targets that it felt forced to issue a binding directive listing vulnerabilities that must be addressed. It did so simply because it is so common for known vulnerabilities to go unpatched.

These vulnerabilities are not unique to government services – any technology environment can be affected.

And here’s the rub: just like government technology environments, your technology estate may be full of vulnerabilities that need remediation. The CISA list would be an excellent place to start fixing things.

And to top it all off, these are not just -potentially- exploitable vulnerabilities.

If you read the directive attently, these are vulnerabilities -currently- being exploited in the wild, meaning that exploit code is either readily available for everyone or being distributed in the less savory corners of the Internet. Either way, these are not just a hypothetical threat anymore.

The hidden message of the CISA directive

It’s not that either you – or tech teams in government – are negligent, or ignorant. It’s just a matter of practical realities. And in practice, tech teams don’t get around to consistently remediating vulnerabilities. Big, obvious, known vulnerabilities such as those listed in the CISA directive can lie waiting for an attacker to exploit simply because tech teams never fixed it.

There are a variety of reasons why it happens, and neglect is rarely one of them. A lack of resources is arguably one of the biggest causes, as technology teams are simply too stretched to test, patch, and otherwise mitigate sufficiently.

There’s the disruption associated with patching too: urgent patches can quickly turn less pressing in the face of stakeholder pushback. So what the CISA directive is really saying is that practical realities mean that there’s an ocean of vulnerabilities that are simply not getting addressed and which are leading to successful exploits.

And, in response, CISA produced what you could call an emergency list simply because of the level of desperation with cybercrime. In other words, the situation is untenable – and the CISA directive is an emergency band-aid, a way to try and cauterize the damage.

Curb disruption and you also boost security

Starting to address the most critical, most exploited vulnerabilities is the obvious answer, and that’s what the CISA list is intended to accomplish. Close behind is throwing more resources at the problem – devoting more time to fixing vulnerabilities is a worthy step.

But these obvious steps quickly run into a wall: fixing and patching causes disruption, and finding a way forward is challenging. And without finding a way past these disruptive effects, the situation may continue to get so bad that we need steps like the CISA directive. Remodeling security operations is the answer.

What can tech teams do? It requires wholesale re-engineering in a way that minimizes patching-related disruption. Redundancy and high availability, for example, can help mitigate some of the worst disruptive effects of vulnerability management.

Utilizing the most advanced security technology also helps. Vulnerability scanners can highlight the most pressing issues to help with prioritization. Live patching by TuxCare is another great tool – because live patching completely removes the need to reboot, which means patching disruption can be essentially eliminated.

And that’s what the CISA directive really means…

Whether you’re in government or the private sector, a rethink is needed because vulnerabilities are piling up so rapidly. The CISA directive underlines how bad things have become. But simply applying more band-aid won’t work – you’ll remediate, and be back in the same situation you were in no time.

So, take the CISA directive as a warning sign. Yes, check whether you’re using any of the software and services on the list and patch accordingly. But, most importantly, think about how you can improve your SecOps – ensuring that you’re more responsive to vulnerabilities by remediating with less disruption. Patch faster with less disruption.

3. Hackers Increasingly Using RTF Template Injection Technique in Phishing Attacks

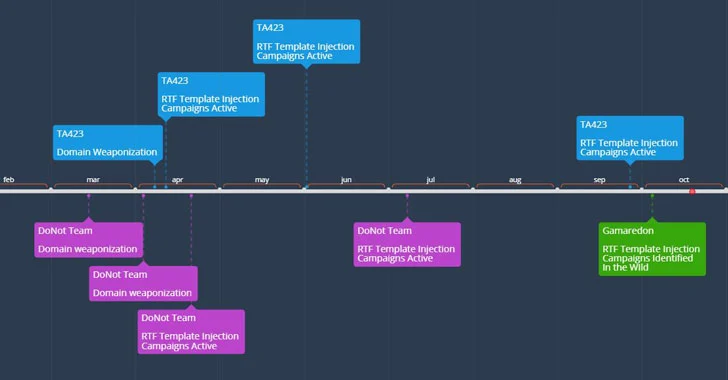

Three different state-sponsored threat actors aligned with China, India, and Russia have been observed adopting a new method called RTF (aka Rich Text Format) template injection as part of their phishing campaigns to deliver malware to targeted systems.

„RTF template injection is a novel technique that is ideal for malicious phishing attachments because it is simple and allows threat actors to retrieve malicious content from a remote URL using an RTF file,” Proofpoint researchers said in a new report shared with The Hacker News.

At the heart of the attack is an RTF file containing decoy content that can be manipulated to enable the retrieval of content, including malicious payloads, hosted at an external URL upon opening an RTF file. Specifically, it leverages the RTF template functionality to alter a document’s formatting properties using a hex editor by specifying a URL resource instead of an accessible file resource destination from which a remote payload may be retrieved.

Put differently, the idea is that attackers can send malicious Microsoft Word documents to targeted victims that appear entirely innocuous but are designed to load malicious code via the template feature remotely. This makes the mechanism a durable and effective method when paired with phishing as an initial delivery vector, the researchers noted.

Thus when an altered RTF file is opened via Microsoft Word, the application will proceed to download the resource from the specified URL prior to displaying the lure content of the file. It’s therefore not surprising that the technique is being increasingly weaponized by threat actors to distribute malware.

Proofpoint said it observed Template injection RTF files linked to the APT groups DoNot Team, Gamaredon, and a Chinese-related APT actor dubbed TA423 as early as February 2021, with the adversaries utilizing the files to target entities in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Ukraine, and those operating in the deep water energy exploration sector in Malaysia via defense-themed and other country-specific lures.

While the DoNot Team has been suspected of carrying out cyber attacks that are aligned with Indian-state interests, Gamaredon was recently outed by Ukrainian law enforcement as an outfit connected to Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) with a propensity for striking public and private sector organizations in the country for harvesting classified information from compromised Windows systems for geopolitical gains.

„The innovation by threat actors to bring this method to a new file type in RTFs represents an expanding surface area of threat for organizations worldwide,” the researchers said. „While this method currently is used by a limited number of APT actors with a range of sophistication, the technique’s effectiveness combined with its ease of use is likely to drive its adoption further across the threat landscape.”

4. New Payment Data Stealing Malware Hides in Nginx Process on Linux Servers

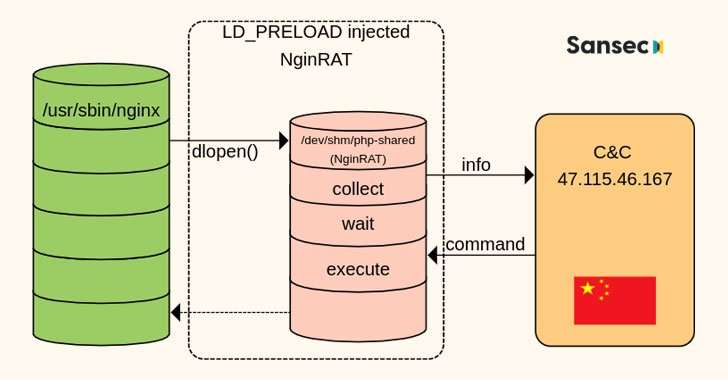

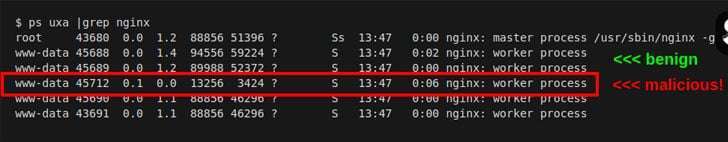

E-commerce platforms in the U.S., Germany, and France have come under attack from a new form of malware that targets Nginx servers in an attempt to masquerade its presence and slip past detection by security solutions.

„This novel code injects itself into a host Nginx application and is nearly invisible,” Sansec Threat Research team said in a new report. „The parasite is used to steal data from eCommerce servers, also known as 'server-side Magecart.'”

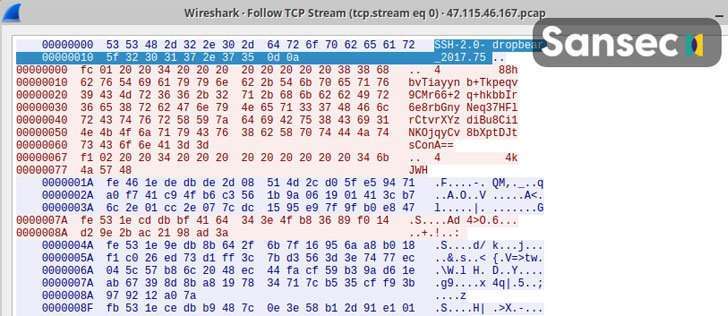

A free and open-source software, Nginx is a web server that can also be used as a reverse proxy, load balancer, mail proxy, and HTTP cache. NginRAT, as the advanced malware is called, works by hijacking a host Nginx application to embed itself into the webserver process.

The remote access trojan itself is delivered via CronRAT, another piece of malware the Dutch cybersecurity firm disclosed last week as hiding its malicious payloads in cron jobs scheduled to execute on February 31st, a non-existent calendar day.

Both CronRAT and NginRAT are designed to provide a remote way into the compromised servers, and the goal of the intrusions is to make server-side modifications to the compromised e-commerce websites in a manner that enable the adversaries to exfiltrate data by skimming online payment forms.

The attacks, collectively known as Magecart or web skimming, are the work of a cybercrime syndicate comprised of dozens of subgroups that are involved in digital credit card theft by exploiting software vulnerabilities to gain access to an online portal’s source code and insert malicious JavaScript code that siphons the data shoppers enter into checkout pages.

„Skimmer groups are growing rapidly and targeting various e-commerce platforms using a variety of ways to remain undetected,” Zscaler researchers noted in an analysis of the latest Magecart trends published earlier this year.

„The latest techniques include compromising vulnerable versions of e-commerce platforms, hosting skimmer scripts on CDNs and cloud services, and using newly registered domains (NRDs) lexically close to any legitimate web service or specific e-commerce store to host malicious skimmer scripts.”

5. Researches Detail 17 Malicious Frameworks Used to Attack Air-Gapped Networks

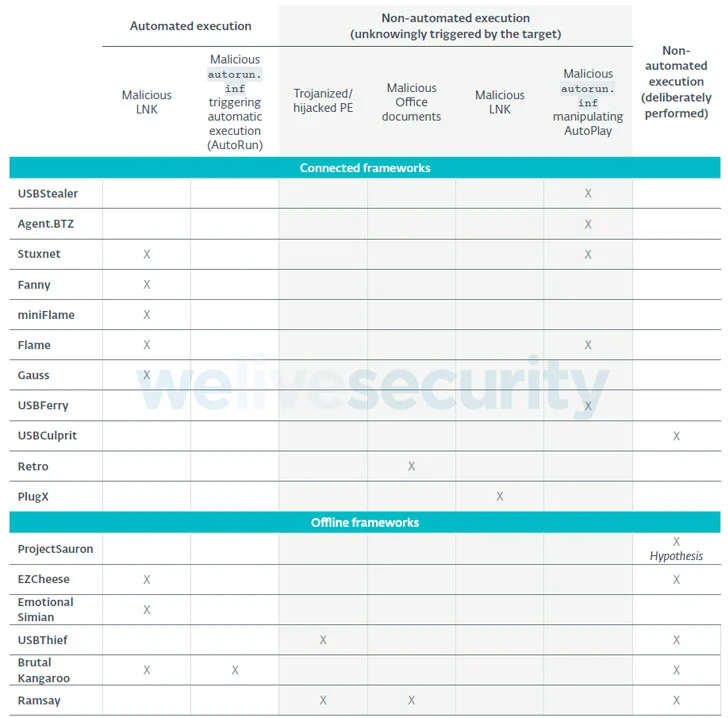

Four different malicious frameworks designed to attack air-gapped networks were detected in the first half of 2020 alone, bringing the total number of such toolkits to 17 and offering adversaries a pathway to cyber espionage and exfiltrate classified information.

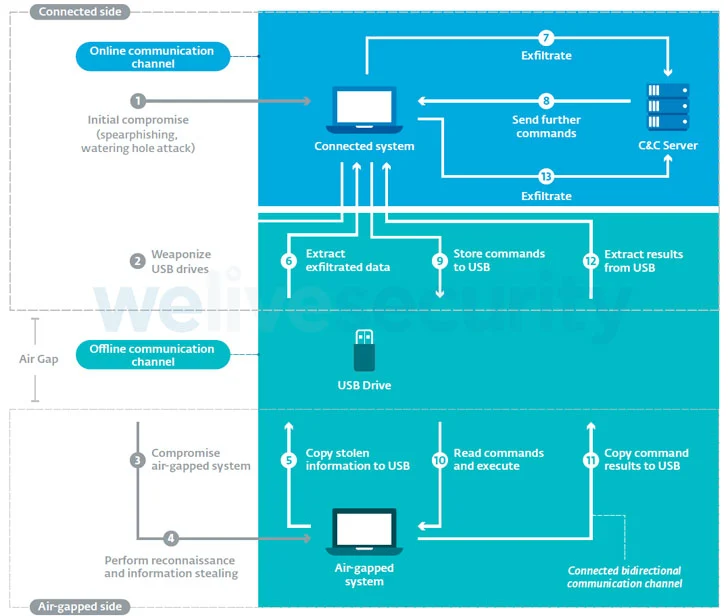

„All frameworks are designed to perform some form of espionage, [and] all the frameworks used USB drives as the physical transmission medium to transfer data in and out of the targeted air-gapped networks,” ESET researchers Alexis Dorais-Joncas and Facundo Muñoz said in a comprehensive study of the frameworks.

Air-gapping is a network security measure designed to prevent unauthorized access to systems by physically isolating them from other unsecured networks, including local area networks and the public internet. This also implies that the only way to transfer data is by connecting a physical device to it, such as USB drives or external hard disks.

Given that the mechanism is one of the most common ways SCADA and industrial control systems (ICS) are protected, APT groups that are typically sponsored or part of nation-state efforts have increasingly set their sights on the critical infrastructure in hopes of infiltrating an air-gapped network with malware so as to surveil targets of interest.

Primarily built to attack Windows-based operating systems, the Slovak cybersecurity firm said that no fewer than 75% of all the frameworks were found leveraging malicious LNK or AutoRun files on USB drives to either carry out the initial compromise of the air-gapped system or to move laterally within the air-gapped network.

Some frameworks that have been attributed to well-known threat actors are as follows —

- Retro (DarkHotel aka APT-C-06 or Dubnium)

- Ramsay (DarkHotel)

- USBStealer (APT28 aka Sednit, Sofacy, or Fancy Bear)

- USBFerry (Tropic Trooper aka APT23 or Pirate Panda)

- Fanny (Equation Group)

- USBCulprit (Goblin Panda aka Hellsing or Cycldek)

- PlugX (Mustang Panda), and

- Agent.BTZ (Turla Group)

„All frameworks have devised their own ways, but they all have one thing in common: with no exception, they all used weaponized USB drives,” the researchers explained. „The main difference between connected and offline frameworks is how the drive is weaponized in the first place.”

While connected frameworks work by deploying a malicious component on the connected system that monitors the insertion of new USB drives and automatically places in them the attack code needed to poison the air-gapped system, offline frameworks like Brutal Kangaroo, EZCheese, and ProjectSauron rely on the attackers deliberately infecting their own USB drives to backdoor the targeted machines.

That said, covert transmission of data out of air-gapped environments without USBs being a common thread remains a challenge. Although a number of methods have been devised to stealthily siphon highly sensitive data by leveraging Ethernet cables, Wi-Fi signals, the computer’s power supply unit, and even changes in LCD screen brightness as novel side-channels, in-the-wild attacks exploiting these techniques have yet to be observed.

As precautions, organizations with critical information systems and sensitive information are recommended to prevent direct email access on connected systems, disable USB ports and sanitize USB drives, restrict file execution on removable drives, and carry out periodic analysis of air-gapped systems for any signs of suspicious activity.

„Maintaining a fully air gapped system comes with the benefits of extra protection,” Dorais-Joncas said. „But just like all other security mechanisms, air gapping is not a silver bullet and does not prevent malicious actors from preying on outdated systems or poor employee habits.”